Hello! I am Matthew Lancellotti, the author of provemath.org.

Provemath began in 2015 when I was tutoring an undergraduate student in a graph theory course at Rutgers University.

I’ve always wanted to write a textbook, but a textbook that was extremely well-written and easy to understand. With experience, I’ve learned that how easy a textbook is to understand depends on multiple factors. It depends on how rigorous the textbook is. It depends on how accurate the textbook is. It depends on what intuitive analogies the textbook calls on to help the reader (user) grasp new concepts. But most importantly, it depends on the reader themselves. Different users have different skills and knowledge. Therefore, there is no such thing as a perfect textbook. I believe that technology can change this by catering content to the user.

For example, if a user reads a sentence that contains a word they do not know, what do they do? They go backwards and try to find the definition of that word. Technology makes this fast by allowing the user to click on the word and be instantly transported to the definition of the word. This is common practice in websites such as Wikipedia.

As a second example, if a user understands a fact, they can record it as “learned”, and technology will automatically present the user with new concepts that they are now capable of learning because they have satisfied the prerequisites. This is a feature of Provemath.

The point is that I wanted to write my math knowledge down in a way that could later be consumed by different users in an efficient way. I needed a place to record my math notes so that I could come back to them later and experience them as if I were reading a “good textbook”. This was the beginning of Provemath. Graph theory and logic helped me to understand that mathematics itself is a Directed Acyclic Graph. Every mathematical fact is a node. Every mathematical definition is a node. The nodes are linked together by directed edges that show which definitions and facts they depend on. This is commonly called a “dependency tree” in computer science.

Let’s walk through some features of Provemath alongside pictures.

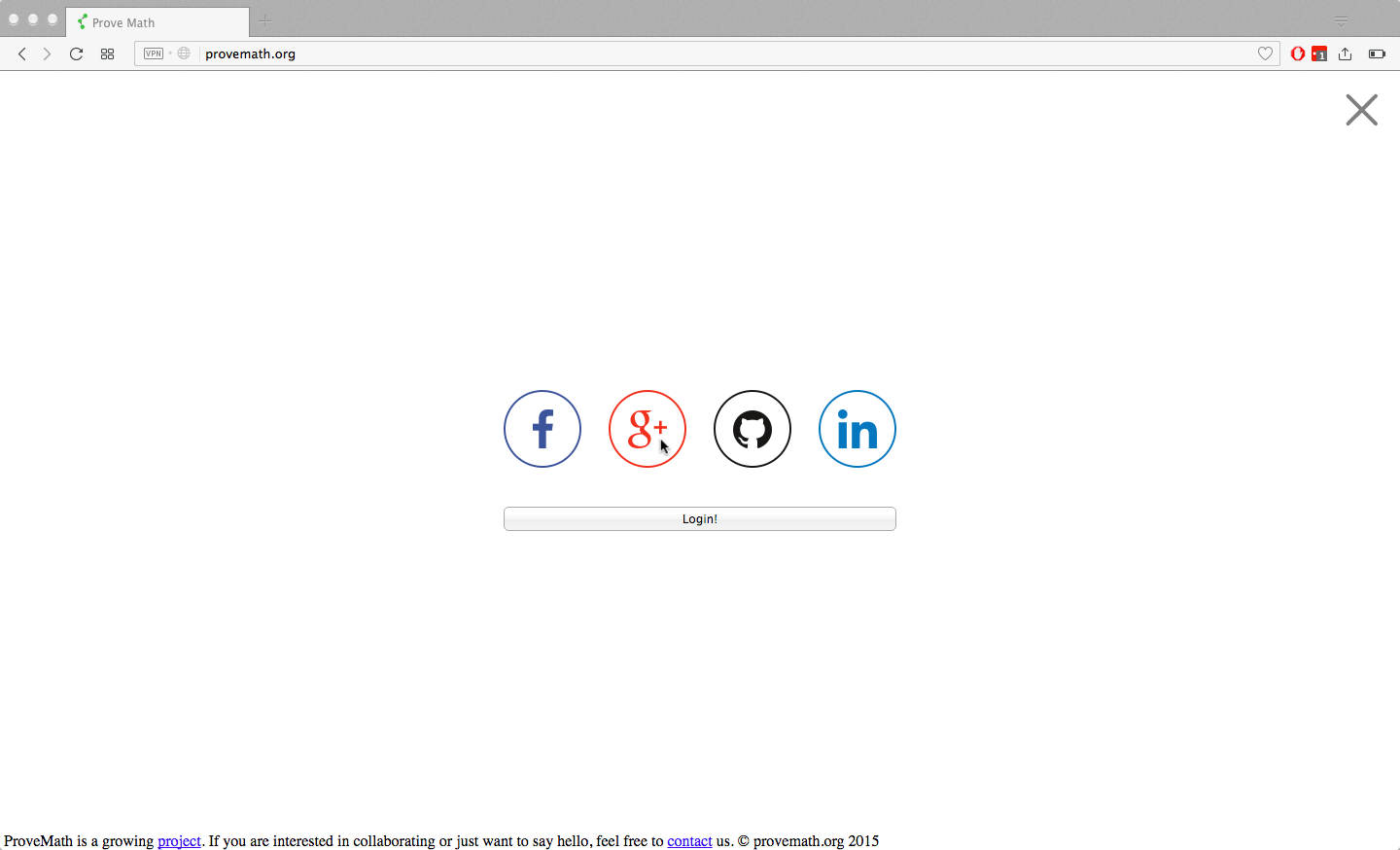

Login

Users can login so that their progress and preferences are saved for future visits. Alternatively, they can click the “X” to not log in:

technical details: Oauth login is used because it is more secure than savings passwords on my server. User progress and preferences are linked to their oauth account number and stored on MongoDB on my server. Users who click the “X” are given a brand new account that is not linked to any Oauth provider. Such accounts can never be logged into again, and are deleted at a later date. This solution has proven to be simpler than treating non-logged in users differently than logged in users, which causes complications in the code and inconsistency in user experiences.

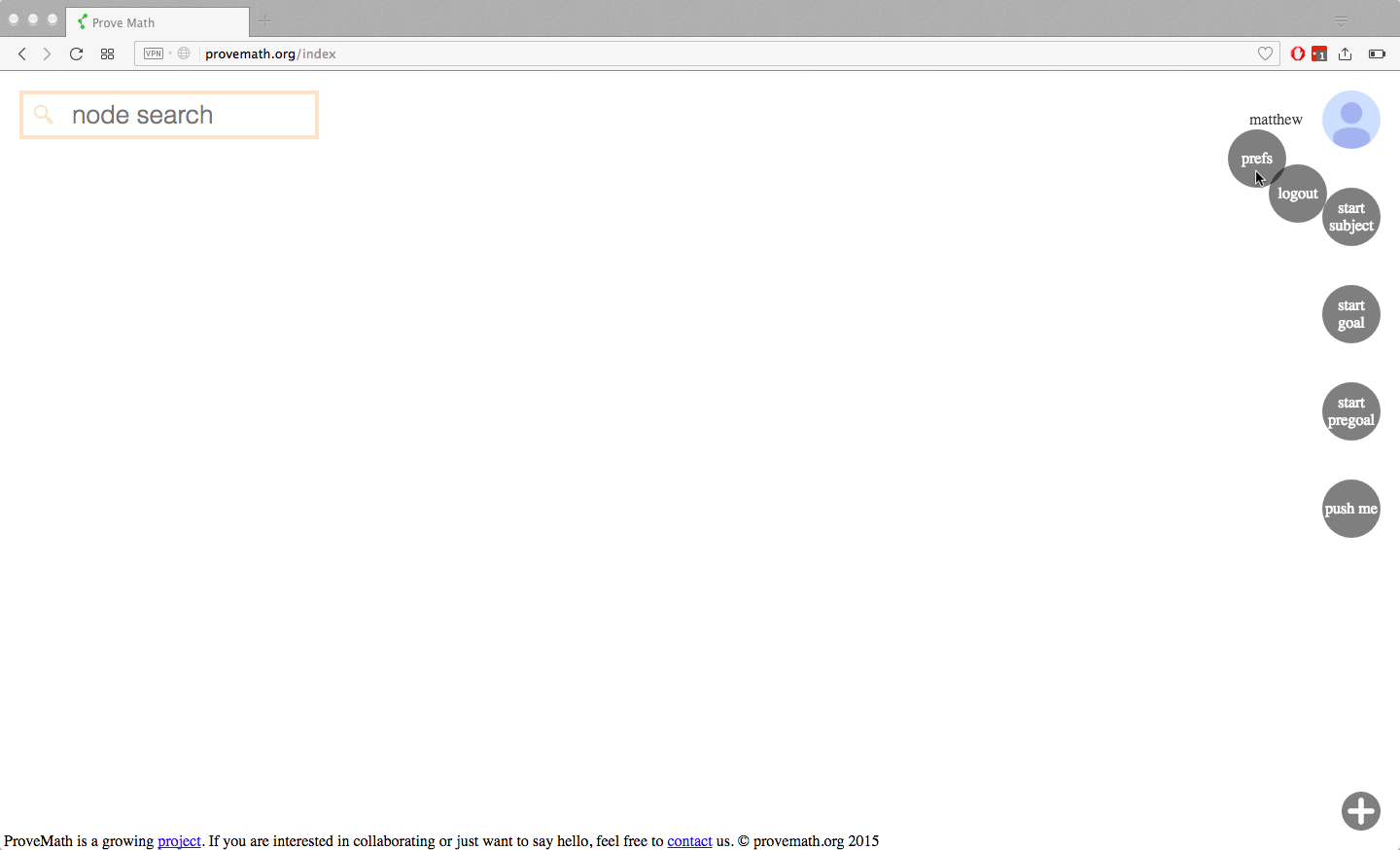

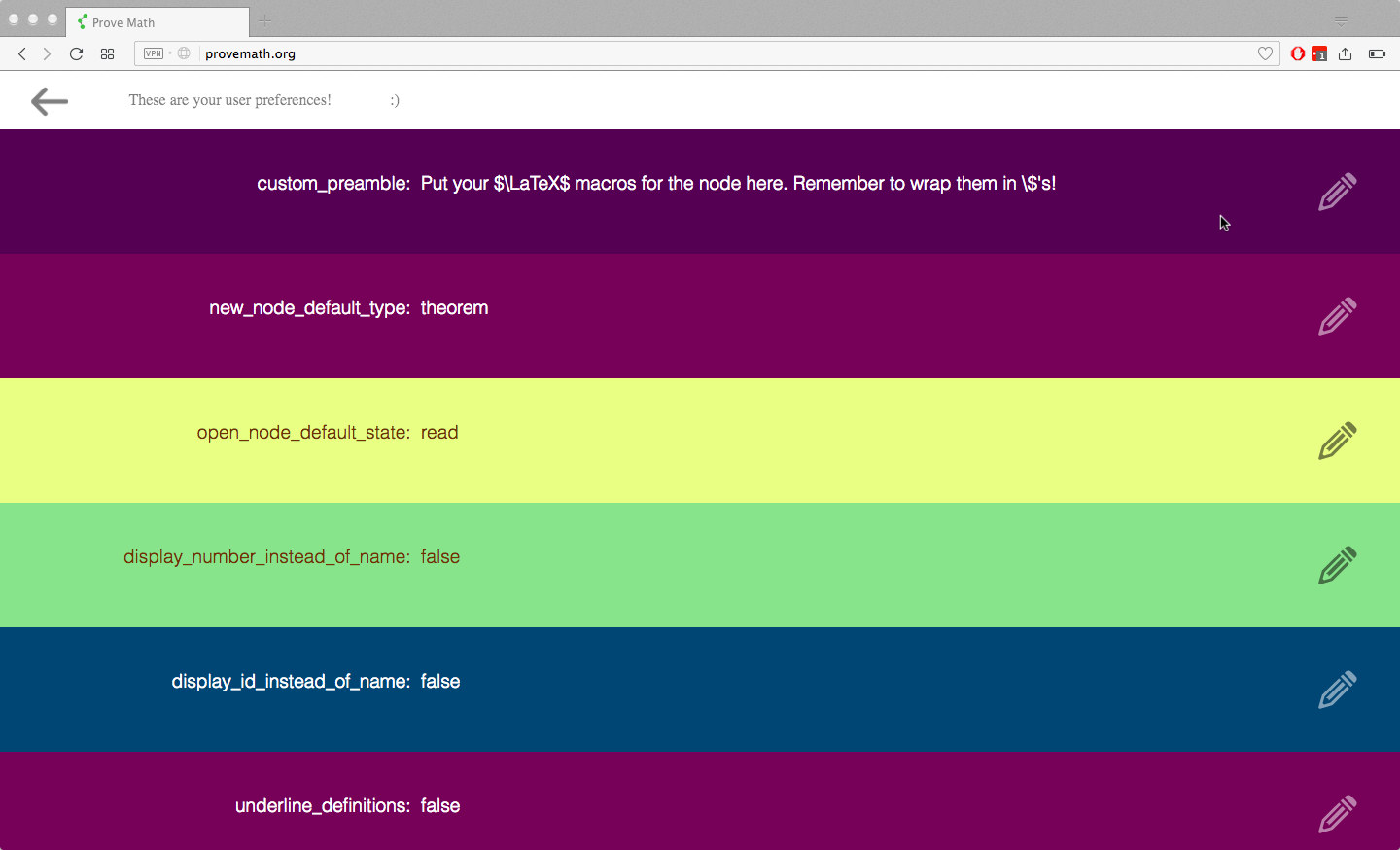

Preferences

Users can edit their preferences. This customizes the experience for the user:

Here are just a few preferences:

- LaTeX preamble

Each node supports LaTeX. LaTeX users typically define macros in a “preamble” of their document that they can later use for convenience. In the same way, each node has a “preamble” where users can define macros that will apply to all content in the node. A user (or content author) can therefore specify a preamble in their preferences that will be automatically added to any new nodes they create. This is a desired convenience especially for somebody adding course material to the site, because it saves time.

- keyboard shortcuts (aka “keycuts”)

A number of keyboard shortcuts give users extra convenience. By default, “ctrl+f” puts the search bar in focus, “ctrl+n” creates a new node, “ctrl+s” saves a node, and “esc” is the same as clicking “x” or a back arrow. These keyboard shortcuts (and some not listed here) can be customized to fit the user’s needs.

Choose a subject

Users select a subject that they want to begin learning. Starting nodes for that subject are sent to the user. User is free to click on those nodes and begin learning at will!!

technical details: A server-level config file contains a dictionary of math “subjects” (as humans classify them) for which their exists content in the database. Math content is NOT partitioned or organized into subjects. All the math material comes from the DB and populates a directed acyclic graph. It is just one big graph. However, if a user says they want to learn “abstract algebra ii”, then I know that this “subject” begins with understanding what a “module” is. Therefore, this is the starting node sent to the user.

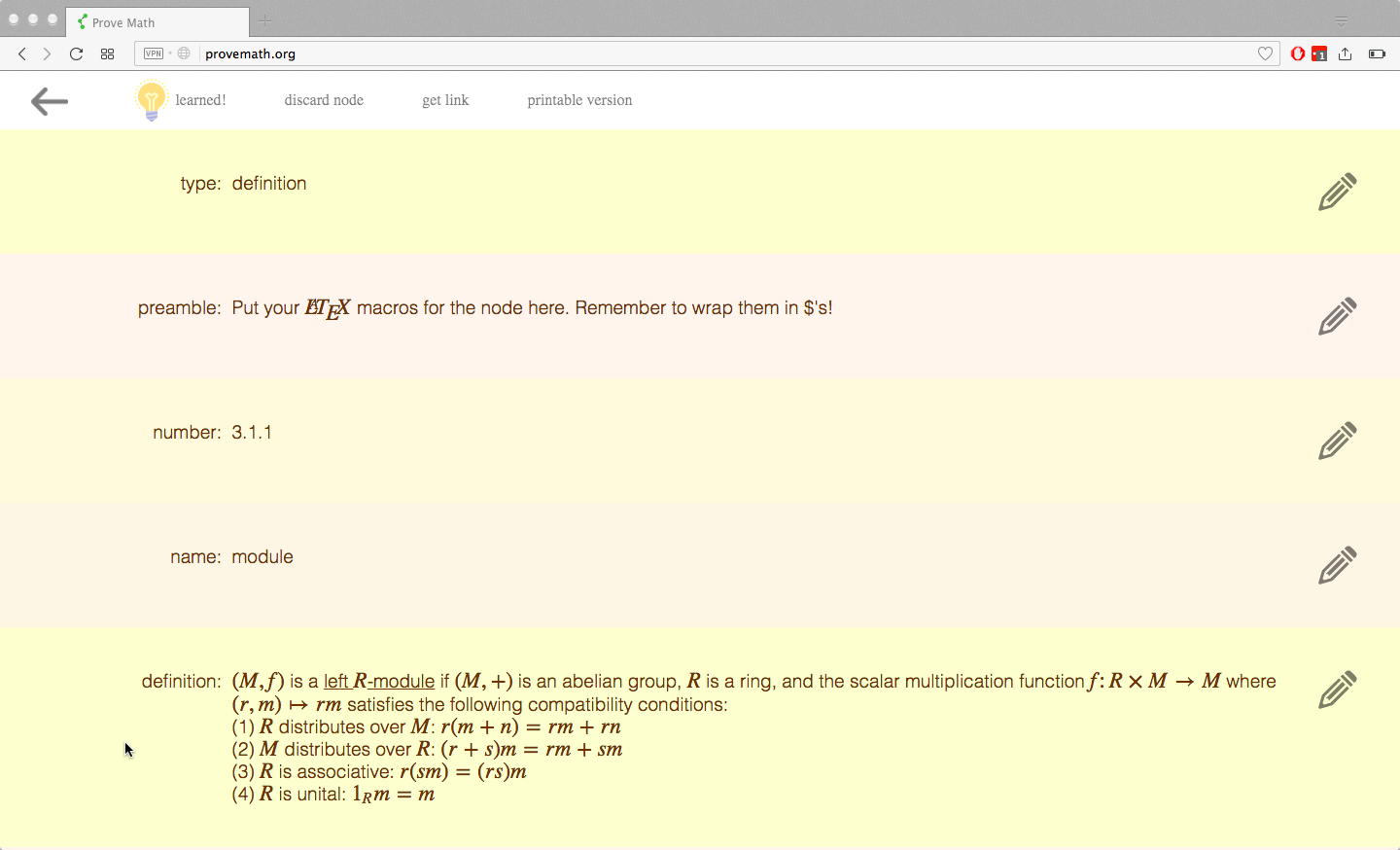

Content display

The user clicks on the node and sees the actual math content. The user reads the content and learns! 🙂

technical details: The node is an object in Javascript, and it is passed to a GUI object called “Blinds” which displays the object as a bunch of rows. The content is written in markdown with MathJax drop-ins, so it is run through a JS markdown implementation and displayed as HTML, and then MathJax runs on the displayed result (unfortunately, MathJax does not yet support being run BEFORE the content is rendered in the DOM, but that support is planned and arriving soon)

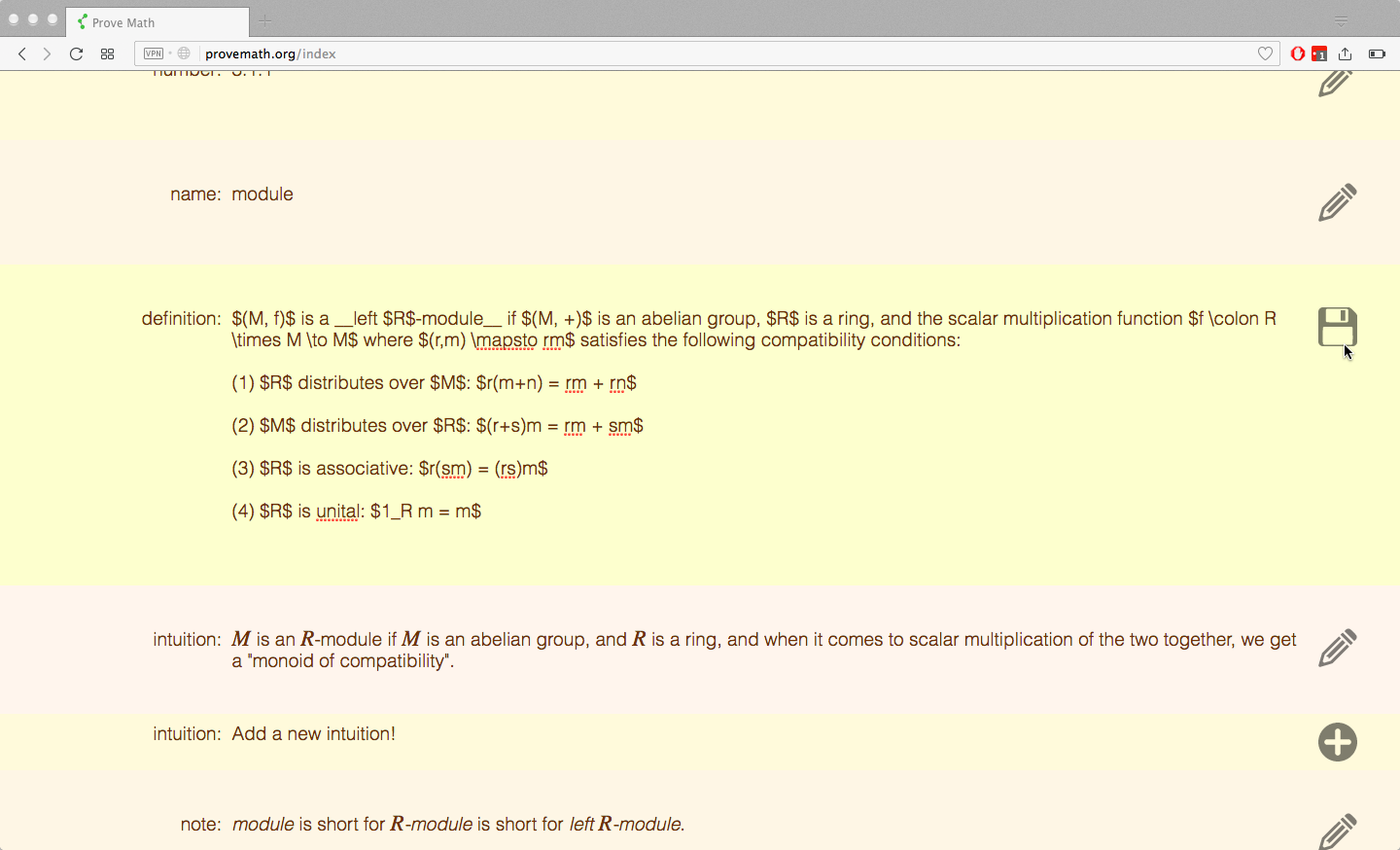

Continuous content improvement

If the user sees a typo (or if the user is an author who is actually WRITING the content), they can click the “edit” button in order to update the content for everyone.

technical details: The original content (before being processed into HTML) is displayed to the user and editable via “contenteditable” in HTML. Upon clicking “save”, the proposed changes are sent to the server and run against error checks and scoring criteria, resulting in a ScoreCard object. Errors cause the ScoreCard to have a failing grade. Other criteria have smaller impacts on the grade and basically suggect changes to the user. If the ScoreCard is a passing grade, the content is accepted into the DB, replacing the old content. The ScoreCard is sent back to the user and the content is updated on the screen.

Directed learning

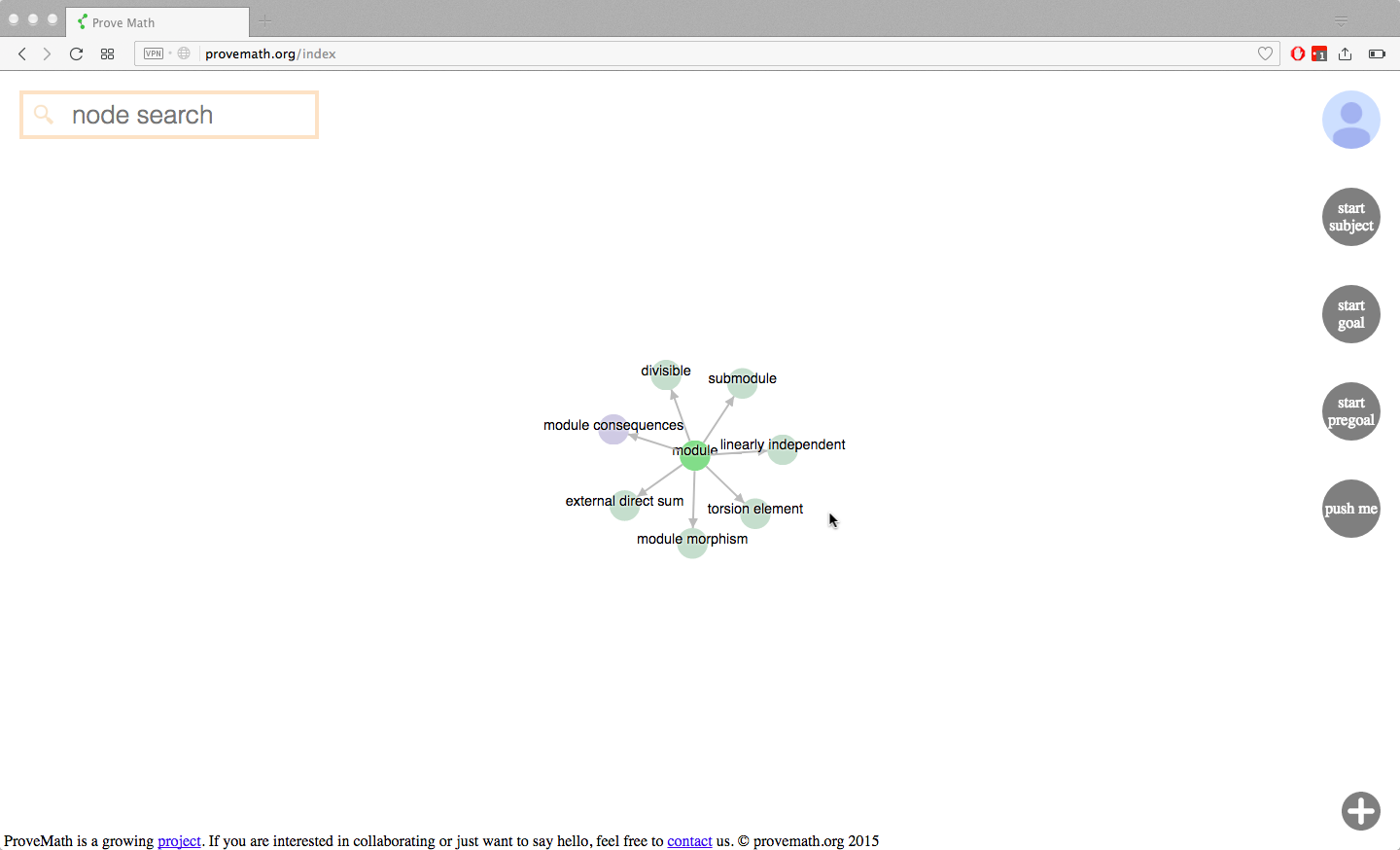

The user now understands the material (woohoo!), so they click the light bulb to mark the node as learned, and the back arrow to return to the graph view. Arriving back in graph view, a surprise is in for the user. New nodes have arrived on the graph!

The now “learned” node shows in bright green. Because the user knows what a “module” is, they are now capable of understanding what a “submodule” is, as well as all of the other nodes that now appeared.

Let’s pretend the user goes ahead and learns what a “submodule” is, and then what an “ideal submodule” is:

Unlike a regular textbook, users are not forced to follow a specific path of learning. But they are still encouraged to learn in a logical order (more than one path of learning is logically valid, and the user can choose within this structure)

technical details: The builtin capabilities of NewtworkX (a Python library which exposes a robust DirectedGraph object) have been extended to include a DAG (DirectedAcyclicGraph) object and many graph algorithms for that object that are specific to our needs. Whenever the user learns, their progress is sent to the server, and algorithms are run against the global DAG object. This results in new material being sent back to the user.

Graph animation

The user takes a look at their options, and possibly moves the graph around / rearranges nodes.

technical details: Data is fed into D3js (Data Driven Documents) using a force-directed-graph visualization. The pieces built for display are SVG, so there is no pixelation. The graph animation has been tweaked and D3 has been patched to dampen node excitement, as to not be too distracting for the user 🙂

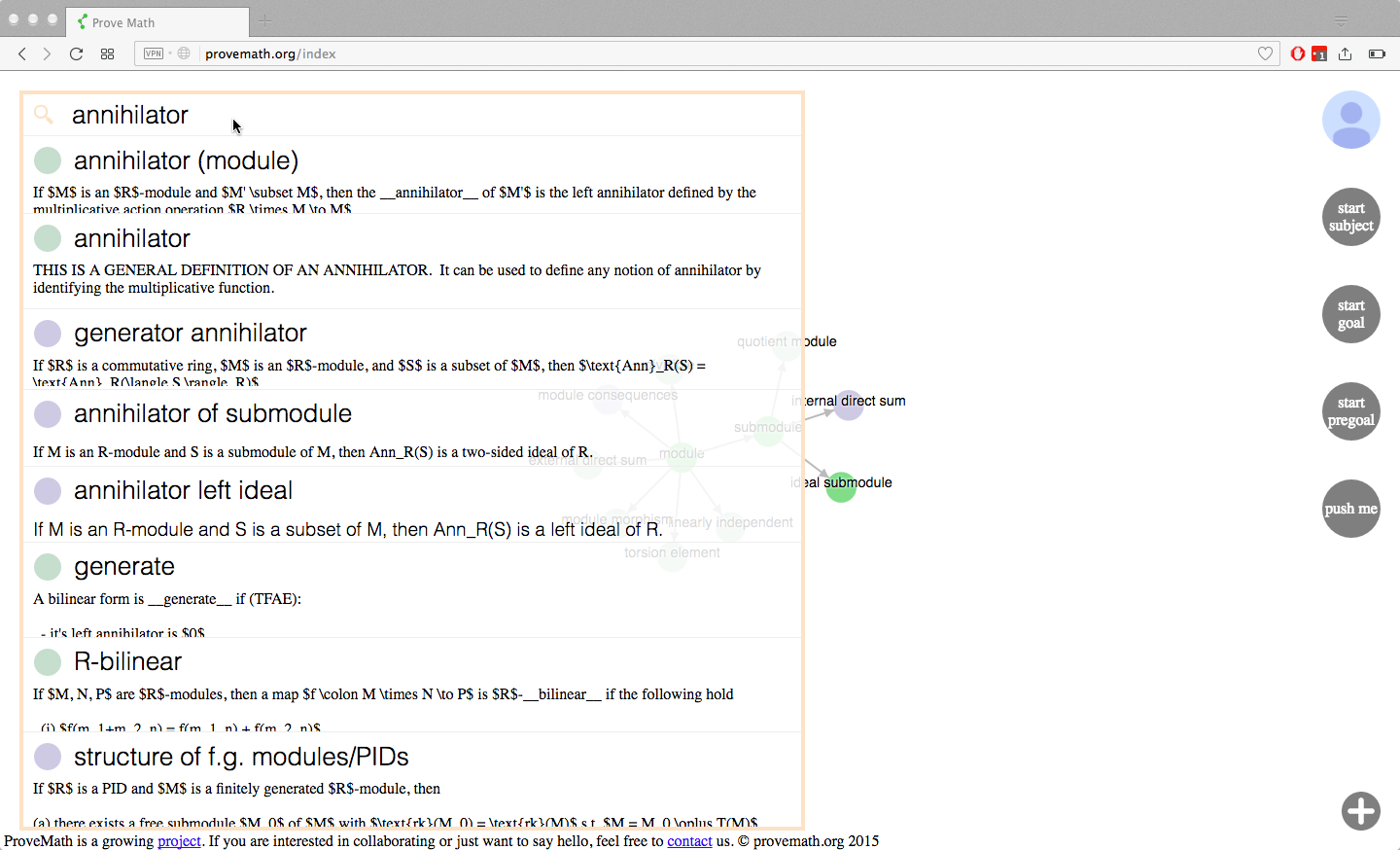

Search

The user continues learning in this fashion. Consider that the user wants to look for a node that isn’t on their current graph. They can use the search feature to find it.

technical details: MongoDB supports a text index for searching purposes. Each node is a single JSON dictionary in the DB. We enable a text index which gives a different weight to each key in the node dictionary (the “name” key of the node gets a much higher weight than, say, the “dependencies” key). Therefore, ALL content of a node is searched, but more weight is given to the node name and node description than other content in the node. The top 15 results are processed into actual Node objects and sent back to the client.

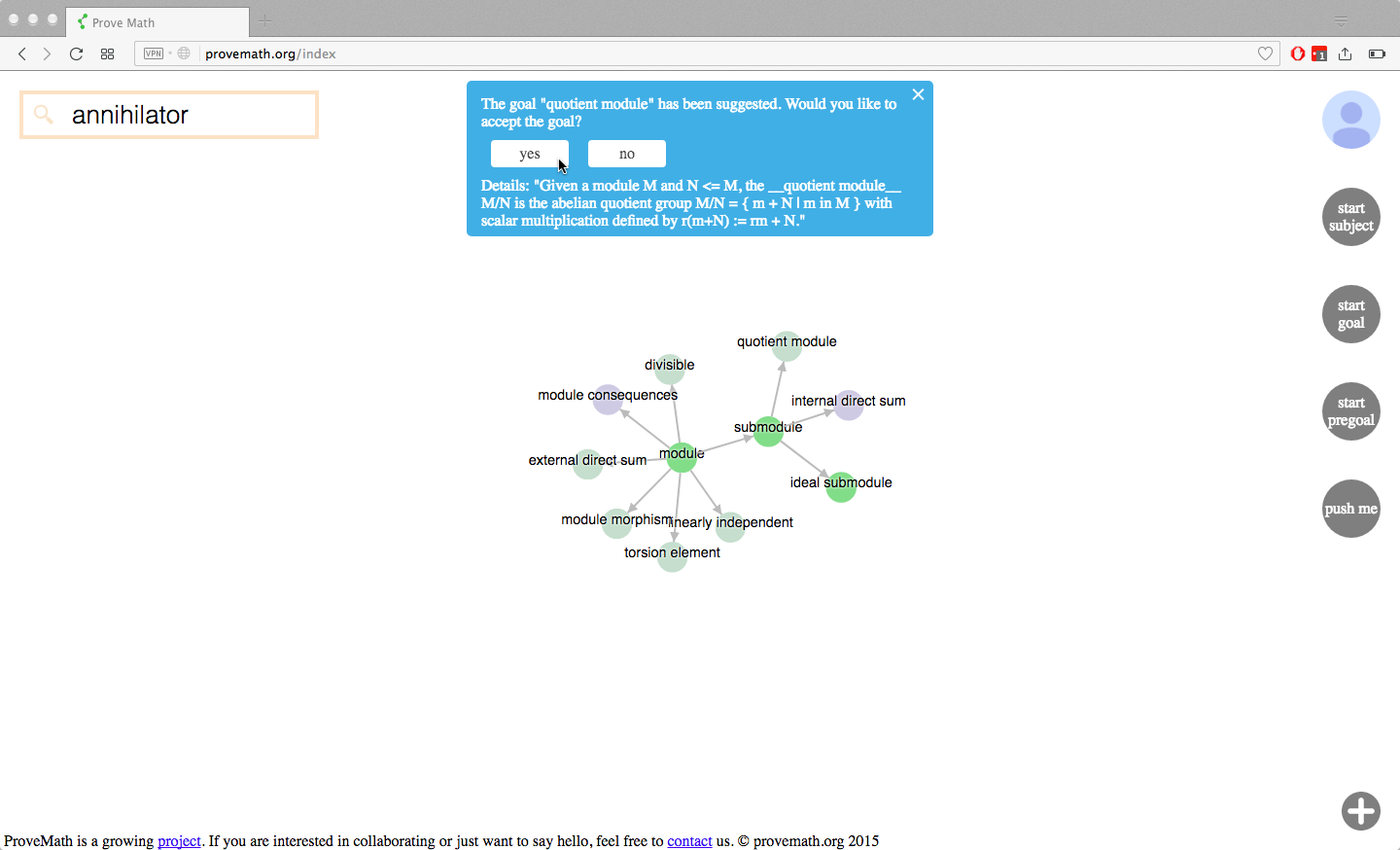

Goals and depth-first learning

What if there is a specific theorem the user wants to learn? The user can set this theorem as a goal, using the “set goal” feature. Part of this feature is still unfinished. For now, a user can click the “set goal” button, and the program will automatically choose a new goal for them. This new goal is chosen in a smart fashion. We encourage “depth first learning” as opposed to “breadth first learning”. So the server finds the deepest thing that they are capable of learning next, and suggests it as their next goal.

technical details: This is one of the most important algorithms in ProveMath. Certain nodes in the DAG are “axioms”, which you can think of as the “sources” of the DAG (although technically there is a distinction between these two). A node’s distance from the set of axioms determines its “depth”. This gives us a way to measure how deep math concepts are, with newer theorems usually being “deeper” than older ones. But we also want users to have a say in which theorems the computer will suggest to the learned. Therefore, nodes are weighted with “importances” that users can vote on. These weights are factored in to the calculation.

Bridging learning

What do we do if the user has knowledge from two separate areas of math? (On the graph, this would look like two disconnected pieces of nodes.) We bridge them together! The server will suggest learning nodes that are close to both separate areas, eventually connecting them together. Research shows that connecting the things we know (or want to learn) to other things we know causes us to remember the knowledge for longer. This feature is planned for the future.

More features in the works:

Voting

Users vote on contibuted content quality, allowing the “best” proof of a theorem, for example, to be listed first. This is similar to what you see on Stack Overflow. (feature in progress)

Curriculum making

A professor, for example, can choose a node which is the end goal of the course he wants to teach. ProveMath retrieves the dependency tree of that node, and the professor trims off the nodes he expects students enrolling in his course to already know. The result is a curriculum for his course, which can be linearly ordered. (feature in progress, almost done)

Printing

Users can view a printable version of any node, so that they can print it out on paper. (Most monitors cause eye-strain, and many learners I know prefer to learn from a physical piece of paper.) Users can also view a printable version of a curriculum, so that they can print out the entire notes for the course in an appropriate linear order. (feature completed)

Sharing

When viewing a node, the user can click on a “share” button which copies a URL to their clipboard. They can send this link to a friend if they want their friend to navigate directly to that node.

technical details: The main website does not consist of separate “pages” because it increases load time. Instead, the website is updated as information evolves. Therefore, this URL must specify the specific node in a query string. When somebody visits the URL, the server processes the query string and sends directions to the client to load that particular node.

Other notable technical details:

- gulp is used to run/kickoff build processes, especially on the JS side

- JS is written in EMCAScript 6 and transpiled into EMCAScript 5 by babel

- CSS is written in Sass and transpiled into CSS3, then augmented via Autoprefixer

- We are using the Tornado web framework, because it supports asynchronous programming (which is a predicted necessity for the future, when the math graph gets really huge)

- We are using Sphinx for documentation, which can be accessed at provemath.org/docs

- Server side in Python3